Nike’s Super Bowl ad: A middle finger to the noise, a kitchen battle cry, and the recipe for winning anyway

Nike gets it. Always has.

Win anyway. Nike doesn’t do subtle. They don’t do polite. They don’t whisper sweet nothings about effort and perseverance they slap you in the face with them. This year’s Super Bowl ad? A masterclass in that philosophy. A raw, punch-in-the-gut manifesto that doesn’t ask for permission, doesn’t beg for validation. It just tells the truth: You can’t win. So win.

Simple. Direct. Unapologetic. The kind of message that makes you stop mid-bite, mid-sip, mid-breath and nod because you know, deep down, it’s true.

It’s the same nonsense we see everywhere, including the kitchen.

Nike’s answer? Win anyway.

Think about it…who do we call chef? The men with their Michelin stars and their white jackets, screaming over the pass like battle commanders. And yet, for centuries, women have been the ones behind the stove, feeding entire generations, keeping entire cultures alive through food. And what do we call them? Home cooks.

This isn’t about feel-good slogans or empty empowerment. It’s about the grit, the sweat, the relentless pursuit of something bigger than yourself. It’s about athletes who refuse to play by the rules that were never made for them in the first place.

It’s Serena Williams smashing records and still being told she’s too emotional. It’s Chloe Kim landing a trick no man or woman has ever done and being called too lucky. It’s every woman who’s been underestimated, second-guessed, or told she doesn’t belong turning around and proving, over and over again, that she damn well does.

It’s the same game. The same moving goalposts. The same whispered (or shouted) doubts. But here’s the thing: the best of them the best of us keep cooking anyway.

Because winning isn’t about applause. It’s about doing the thing. It’s about putting in the hours, the sweat, the blood, the tears, whether anyone is watching or not. It’s about showing up, day after day, knowing the world might never give you the credit you deserve and doing it anyway.

And that’s where the magic happens.

Nike doesn’t just sell shoes. It sells rebellion, self-belief, and the kind of defiance that makes history. And this ad? It’s a battle cry.

So, yeah. You can’t win.

So, let’s cook something that embodies this attitude something bold, resilient, and unapologetically good. Something like Spicy chicken (or prawn) garlic butter pasta with lemon and herbs - a dish that doesn’t ask for permission, doesn’t play by the rules, and leaves a lasting impression, just like that ad.

The Lesson?

Ignore the noise. Make the thing. Take up space. Be too much. Be not enough.

And then win anyway.

From haggis to heaven: A Glasgow culinary crawl worth raising a dram

Walking the streets of Glasgow feels like stepping into a narrative, each cobblestone and corner store humming with stories. The city—pedestrian-friendly and buzzing with an understated charm—invites exploration. It’s a place that asks you to slow down, not because it’s sleepy, but because the treasures here demand savoring. This is Glasgow, bold and alive, where the bite of a winter evening only sharpens your appetite for what’s to come.

I arrived just ahead of Burns Night, that ode to Scotland’s bard and, perhaps more importantly, a celebration of the culinary soul of this country. My first walk took me to the Necropolis, a sprawling Victorian cemetery perched above the city. It’s not a morbid experience but a meditative one. Each monument stands as a testament to lives lived, ambitions chased, and dreams achieved or lost. From its heights, Glasgow stretches out like a story yet to be read, the River Clyde slicing through its heart. The sheer scale of the Necropolis, with its ornate tombs and intricate carvings, speaks to a city with deep roots and an appreciation for its past.

The streets below buzzed with life as I made my way back into the heart of the city. Glasgow is a mosaic of contrasts: elegant sandstone buildings alongside modern glass facades, high-end boutiques nestled next to quirky vintage shops. The pedestrian-friendly nature of the city makes it easy to stumble upon hidden gems. Small bookstores, artisanal coffee shops, and music venues line the streets, each offering its own slice of Glasgow’s character. There’s a sense of authenticity here—a city that doesn’t try to be anything but itself.

As night fell, the city transformed. The warm glow of pub windows spilled onto the streets, and laughter mingled with the sharp crackle of cold air. Glasgow’s culinary scene doesn’t just feed you; it challenges and seduces you. My evening destination: The Pipers' Tryst Restaurant. A gem tucked into the National Piping Centre, it’s the kind of place that whispers rather than shouts, and its quiet confidence is well-earned.

I started with haggis, neeps, and tatties. Let’s be honest: haggis doesn’t win beauty contests. But this was art—a modest tower of earthy, peppery perfection draped in a whisky cream sauce so divine it could make a grown man weep. The whisky’s warmth and the creamy richness balanced the haggis’s boldness, with the sweet tang of turnips (neeps) and buttery mash (tatties) rounding out each bite. It was unapologetically Scottish and unapologetically brilliant.

The main course was a study in restraint and elegance: a salmon fillet, seared to a golden crisp, atop a potato croquette that had the crunch of a good story’s climax. Peas, vibrant and fresh, punctuated the plate like a bright plot twist. The balance was perfect, each element complementing the others without overpowering. It was Scotland on a plate—bold yet refined, comforting yet surprising. The salmon’s flaky texture and the croquette’s satisfying bite were matched by the sweetness of the peas, creating a dish that lingered in my mind long after the plate was cleared.

And then came dessert: cranachan. A dessert that’s part romance, part celebration. Layers of whipped cream kissed with whisky, honey, and toasted oats danced with tart raspberries. It was light and indulgent all at once, a fitting crescendo to an unforgettable meal. Each spoonful felt like a toast to the evening, a celebration of Scotland’s culinary heritage wrapped in sweetness and warmth.

But the meal was only part of the story. Glasgow’s dining scene isn’t just about the food; it’s about the people who bring it to life. At The Pipers' Tryst, the staff’s passion for showcasing Scottish cuisine was evident. They spoke of the ingredients and traditions with the kind of reverence usually reserved for folklore. It’s this sense of pride and authenticity that makes dining in Glasgow so special.

Walking back to my hotel, I felt the kind of contentment that only comes from being well-fed and well-welcomed. The streets, quieter now, still carried whispers of the day’s bustle. I stopped to admire the lit-up façades of the buildings, their warm glow reflecting the city’s unpretentious beauty. Glasgow isn’t just a city you visit; it’s a city you feel. Its culinary scene mirrors its people: unpretentious, warm, and fiercely proud of its roots. Burns Night or not, Glasgow has poetry in its soul and its kitchens. And for that, I’ll raise a glass—slàinte mhath.

Broth of the wild: How Pho stole my soul on Somerset Street.

There’s something about a smell. The way it punches you in the gut and tickles your brain before you’ve even crossed the threshold. That was my first introduction to Pho Thu Do on Somerset Street in Ottawa. I was fresh-faced, working for Environment Canada, and clueless about what lay beyond the unassuming door of that Vietnamese restaurant. My boss, a culinary Sherpa of sorts, decided it was time for me to get an education—not in climate science, but in broth, noodles, and the kind of alchemy that happens when you let simple ingredients sing together.

The smell hit me first: sweet, beefy, and impossibly rich, like an embrace from a kitchen you didn’t know you missed. My mouth watered, my stomach growled, and I knew this wasn’t just lunch—it was going to be a revelation.

We were ushered to a small table, already set with green tea and a basket brimming with large wooden spoons and chopsticks. A cluster of sauces—sriracha, hoisin, something fermented—hinted at mysteries to come. I didn’t even know how to order, so I leaned on my boss’s experience. “Just get what I get,” he said, smiling.

Enter the special. A bowl of pho so unapologetically loaded it felt like a dare. Rare beef, fatty brisket, tendon, tripe, beef balls, chicken, and—why the hell not—a quail egg. This wasn’t just soup. It was a microcosm of flavor, texture, and tradition, cradled in a steaming, translucent broth.

The server brought out a plate piled high with fresh bean sprouts, dandelion leaves, Thai basil, and Birds Eye chilies. I had no idea what to do with it. Was this a garnish? A side salad? My boss and the other diners started shoving it all into their bowls like it was second nature. When in Rome—or in this case, Saigon via Ottawa—I followed suit, plunging the greens and sprouts into the soup and watching them soften and meld into the broth.

I took my first bite.

Words like “delicious” or “tasty” don’t even begin to cut it. The broth was clean but complex, a silky caress of savory umami punctuated by the snap of chilies and the heady perfume of basil. The meats—tender, gelatinous, chewy—each brought their own story to the table. Even the tripe, something I’d never willingly put in my mouth before, melted into the experience, its texture a counterpoint to the tender beef and slurpy noodles.

This wasn’t just eating; it was participating. I dipped, stirred, tasted, and adjusted with lime and sauces until I found my own perfect balance. It felt like being handed the controls to a jet and told to fly.

That meal ruined me—in the best way. Every other bowl of soup I’d had up until that moment was child’s play. Pho wasn’t just a dish; it was an epiphany. And now, years later, as I stand over a pot of simmering broth, I still chase that first taste. I’ll never fully replicate it, but that’s the beauty of it. It was more than the ingredients or the recipe. It was the place, the company, the moment.

Food like that isn’t just about sustenance. It’s a gateway to another world—a world of flavor, culture, and, yes, even love. Because after that first bowl of pho, I was hooked.

Somerset Street, PHO THU DO. It’s where I learned that soup could be a religion. And I’ve been a devout follower ever since.

Absinthe, shawarma, and somersaults: A very Budapest New Years tale

There’s something about New Year’s in Budapest—a city that wears its scars like a badge of honour. The past is etched into every street, every corner, every ruin. And on one particular frigid New Year’s Day, I found myself chasing ghosts and stumbling into magic.

It started innocently enough. We’d warmed our bones with a steaming bowl of Hungarian goulash, the kind that doesn’t just feed you but wraps you in a thick, paprika-scented blanket of comfort. Walking the dark streets with my boyfriend, the city felt like a mystery we were meant to unravel—cobblestones slick with ice, air so cold it bit at your face.

Ahead of us, two men shuffled through the darkness, looking like they’d just crawled out of a Hemingway novel. Ragged coats, hunched shoulders, the kind of disheveled that makes you wonder about the story. They disappeared through what looked like a butcher’s plastic curtain, the kind that promises nothing good lies beyond.

What did I do? Follow, obviously. To my boyfriend’s absolute horror.

“Are you insane? This is how we die,” he hissed. But I was already through the curtain, stepping into another world.

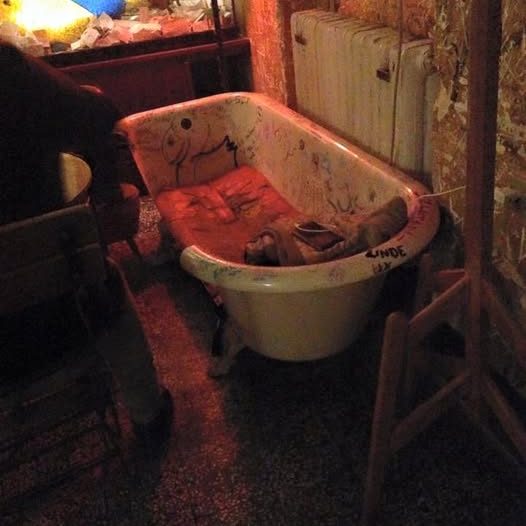

Szimpla Kert. The first and most famous ruin bar in Budapest. Calling it a bar feels like calling the Grand Canyon a hole in the ground. It was a bombed-out factory building transformed into a labyrinth of pure chaos and creativity. A place where every piece of debris, every rusted remnant, had been given a second chance at life.

Bathtubs and toilets served as chairs. An old Trabant—a car that’s more Cold War relic than vehicle make of paper fibre and phenolic resin—was parked in the middle of the room, repurposed as a lounge. The walls were a kaleidoscope of color, a jumble of graffiti and fairy lights that shouldn’t work but did. It was like walking into the mind of a mad artist who’d decided that ruin was just another word for opportunity.

The drinks? Absinthe. Lots of it. The green fairy flowed freely, her mischief slipping into every glass. By the second round, I was convinced this place wasn’t just a bar; it was a portal to some other dimension where rules didn’t apply. Time didn’t matter, and the only thing you had to do was let go.

We drank. We explored. We drank some more. The labyrinth swallowed us whole, spitting us out into hidden corners where strangers became friends and music seemed to seep from the very walls.

Hours later, or maybe it was minutes—who can say? Absinthe has a way of bending reality—we stumbled back onto the icy streets. Finding the hotel felt like a miracle, but not before one last detour that turned out to be the cherry on top of an already wild night.

On the way back to the hotel, we stumbled across a tiny, brightly lit shawarma stand. The aroma alone was enough to draw us in. My boyfriend, used to British doner kebabs drowned in sickly sweet sauce, wasn’t expecting much. But this—this was different. The garlicky richness, the tang of pickled turnip, the way it all came together in a warm, pillowy wrap—it was a revelation.

He devoured his before I’d even taken my second bite. And then, without a shred of shame, he reached over, snatched mine, and inhaled it like a starving man. I barely had time to protest. It was both infuriating and hilarious, a perfect snapshot of a night that seemed to exist outside the normal rules of decorum.

Finding the hotel after that was a blur, a mix of laughter and the lingering taste of garlic on our lips. By the time we reached the hallway, the absinthe had taken full control, and we found ourselves doing somersaults on the way to our room.

That’s the thing about Budapest. It’s a city that dares you to step into the unknown, to follow strangers through plastic curtains, to sit in a bathtub and toast to the absurdity of it all. And on that New Year’s, it gave me a story that’ll outlast a thousand hangovers.

Szimpla Kert isn’t just a bar. It’s a reminder that sometimes, the best memories are made when you ignore the fear, take the leap, and let the city show you what it’s made of. And if you’re lucky, it’ll leave you with more than just a headache the next morning. It’ll leave you with a story.

Gravy wars and Tupperware regret: The post-Christmas kitchen hangover

Christmas, for those of us who revel in the kitchen, is a battlefield. It’s where we flex, where we bleed, and where we pour every ounce of ourselves into meals that people will talk about until the next snow falls.

The house is too quiet. The last echoes of clinking glasses and scraping forks have faded into the ether. A pall of stillness hangs heavy, like the fog of a morning after, thick with regret and lingering satisfaction. Christmas has come and gone, leaving only the faint aroma of roasted turkey and the ghosts of meals past to haunt the kitchen.

There’s a certain melancholy to the post-Christmas letdown, and it’s not just the mountain of dishes waiting in the sink. It’s the end of a grand performance, the curtain call on weeks of meticulous planning, prepping, and execution. Cooking for the holidays is theatre — messy, chaotic, soul-affirming theatre — and this year, the production was nothing short of spectacular.

It started with the turkey. Not just any turkey, but one stuffed with my dad’s legendary sausage and rice stuffing. It’s a recipe steeped in nostalgia and mystery, each spoonful a taste of childhood - a recipe that’s less written down and more tattooed on my soul. Then there was my mom’s French Canadian tourtière, a glorious ode to meat and spice, its flaky crust breaking apart to reveal a filling that whispered of snowy winters and warm kitchens. We glazed a ham until it glistened like a jewel, candied and caramelized to perfection. Even the humble meatloaf made its debut, proving that simplicity can be sublime when done right - like an underdog showing up to the feast and blowing everyone away.

And then there was the gravy.

Oh, the gravy. Not the slapdash sort you throw together at the last minute while the turkey rests. No, this gravy was an opus. Bones slow-roasted until their marrow wept, a stock pot simmering for days, fed like some sacred flame with vegetable trimmings—a leek here, a carrot there. A symphony of savouriness that culminated in what can only be described as liquid gold. By Christmas Day, it was transcendent, a velvet elixir that tied the entire meal together. People wept. Angels might’ve sung.

Of course, the table groaned under all the trimmings: Duck-fat roasted potatoes emerged from the oven, their edges golden and crisp. Sweet potato gratin offered a creamy, caramelized counterpoint so rich it felt criminal. Brussels sprouts, kissed with balsamic and bacon, defied every childhood prejudice against them, so good you almost felt bad for the sprout’s bad PR. Roasted carrots and parsnips brought an earthy sweetness. And cranberry sauce, but not the gelatinous cylinder you hide on the plate. No, this was the real stuff—tart cranberries mellowed with maple syrup, like the forest decided to join the party.

For days, we cooked. For hours, we ate. And then it ended. It was a feast to end all feasts, the kind of meal that makes you feel alive even as it threatens to lull you into a food coma.

The post-Christmas letdown is as inevitable as it is cruel. The leftovers, no matter how glorious on Boxing Day, become a chore by day three. The kitchen, once alive with the hiss of roasting meat and the sharp clatter of knives, now feels too quiet. The fridge, packed to its breaking point, becomes a minefield of cling film and foil-wrapped regret. And you? You’re left staring at a sink full of dishes and a pile of Tupperware, wondering if it was all worth it.

Spoiler: it was.

Post-Christmas is the hangover of the culinary calendar. The thrill of creation is gone, replaced by the muted satisfaction of knowing you gave it everything you had. It’s a strange emptiness, a void that no reheated turkey leg or microwaved ham slice can fill.

But maybe that’s the point. These moments of quiet reflection, the comedown after the high, are what make the next feast worth chasing. The post-Christmas letdown isn’t an ending; it’s a reset, a time to dream of new recipes, new challenges, new reasons to gather around the table.

Because that’s the thing about the feast. It’s not just about the food—though the food was, unquestionably, extraordinary. It’s about the people who gathered around it, the stories shared, the laughter that mingled with the clink of glasses. It’s about that fleeting moment when everything feels right, even if only for a night.

So here I sit, sipping a glass of wine in the stillness, staring at a kitchen that looks like it survived a tornado. The dishes will get done, the fridge will be emptied, and life will return to its usual rhythm. But for now, I’ll savour the silence, the echoes of laughter and clinking glasses still ringing in my ears. After all, the best meals aren’t just about the food — they’re about the stories, the people, and the fleeting moments of magic that linger long after the plates are cleared.

The Fallout paradise of Goa’s Beach Hut

Goa’s beach huts are not for everyone. They aren’t polished resorts or boutique hotels. No sleek infinity pools or white-linen tablecloths here. Instead, these makeshift shacks, teetering on the edge of collapse, are the kind of places that might turn off anyone too squeamish about splinters, rust, or the general aesthetic of a post-apocalyptic settlement. Fallout fans would feel right at home—the place looks ripped straight out of the game.

The huts are cobbled together from whatever scraps the sea didn’t claim—wooden planks, corrugated metal, and an assortment of military-grade bunks, probably from a bygone era of conflict or shipwrecks. Bathrooms are an adventure all their own. You walk through dimly lit corridors patched with tarps and plastic sheets, always with the faint, rusty tang of salt in the air. These spaces scream survival and ingenuity in the face of nature’s relentless wear and tear. And somehow, in their shabbiness, they are a thing of beauty.

This isn’t a place that panders to creature comforts. It’s raw, it’s real, and it’s a reminder that sometimes the roughest settings can offer the richest experiences.

The beach huts are where you go to eat. Really eat.

I think I’ve made my way through every single menu, from the chalkboard specials to the laminated sheets sticky with years of sunblock and sand. You start simple, maybe a mushroom chilly that’s all fire and tang, the kind of heat that sears your tongue but leaves you going back for more. Then there’s the chicken dragon chilly—a dish so fiercely spiced and unapologetic it feels like it’s daring you to quit. You won’t.

Tandoori chicken here tastes like it’s kissed by the gods of fire themselves, the charred, smoky crust giving way to tender, spiced meat. Vindaloos will make you sweat and cry, but you’ll be grinning like an idiot. And then there’s the Love Shack special: murg masalan. This is no ordinary chicken curry. It’s deep and rich, with a complexity that makes you want to stop talking and just let your taste buds do the work.

Today, I tried something new. A lassi. I started with a sweet lassi—simple, refreshing, the kind of drink that feels like a balm for the inferno in your mouth. Then I graduated to a lassi with Old Monk rum. Divine isn’t a strong enough word for what that was. Sweet and creamy with the heady, caramel warmth of the rum. It’s a drink you sip slowly, letting the world around you blur a little.

This place, with its crumbling charm and makeshift brilliance, doesn’t just feed you. It envelops you. It’s an experience that strips away the unnecessary and focuses on what matters: good food, strong drinks, and the beauty of imperfection.

The beach huts of Goa may look like the end of the world, but for those who venture in, they’re just the beginning of something extraordinary.

A good pickling, politics, and a perfect curry: A night at the Love Shack

There are places that transcend the mere act of dining—where the food, the ambiance, and the people come together in an alchemy that borders on the magical. The Love Shack, perched on the golden sands of Calangute Beach, is one of those places.

You don’t stumble upon the Love Shack by accident. You find it because someone, a fellow traveler or local, tells you about it in a voice tinged with reverence. “You have to check out my place… The Love Shack,” they say, eyes lighting up. And so, because you just got off a 10 hour flight, you’re exhausted, jet lagged and starving, you go.

From the moment you step in, you’re struck by the easy, unpretentious vibe. There are no gimmicks here—just open-air seating under a thatched roof, the ocean breeze kissing your skin, and the rhythmic crash of waves as a backdrop. The staff greet you like an old friend who’s been gone too long, not a customer. That warmth sets the tone for the entire experience.

The menu is extensive, but you know why you’re here. The house curry—Murg Masalan—is nothing short of a masterpiece. It arrives at the table, steam curling in fragrant tendrils that speak of hours spent perfecting the balance of spices. The first bite is transformative. Tender chicken luxuriates in a rich gravy infused with tamarind, garlic, ginger and a whisper of star anise. It’s bold without being brash, comforting yet complex, with layers of flavor that linger long after the last bite.

The dish is served with fluffy, fragrant, multicoloured basmati rice and a garlic roti so perfectly charred you’d think it was pulled from the fires of a beachside tandoor. The combination is pure magic. This isn’t just food; it’s a love letter to Goa’s culinary heritage, signed and sealed by a kitchen team that clearly knows what they’re doing.

But what elevates the Love Shack from great to unforgettable is the service. These folks don’t just bring food to your table—they make you feel like family. Whether it’s offering thoughtful recommendations, adjusting a spice level to your liking, or sharing stories about Goa’s hidden gems, their attention to detail is flawless. They work with an understated elegance that leaves you feeling both pampered and completely at home.

And then there was Yuri (at least, I think that was what his name was). Halfway through my second beer—a crisp Kingfisher that pairs perfectly with the spice of the Murg Masalan—he appeared at our table. A burly, sunburned Russian who smelled faintly of pickles and vodka, Yuri introduced himself with a cheerful handshake and proceeded to launch into a spirited monologue about geopolitics. He spoke in heavily accented English, punctuating his points with toasts and fist bulbs that I couldn’t help but join.

Somewhere between a heated discussion about post-Soviet economics and his impassioned praise of Goa’s beaches, Yuri shared his own theory about what makes the Love Shack special. “This place,” he said, gesturing with a piece of naan, “it is not about food or drink. It is about people. We come here to forget borders, forget nonsense. We are all friends.”

And he was right. By the end of the night, I had learned more about Russian pickling techniques than I ever thought possible, promised to visit St. Petersburg someday, and shared a plate of prawns Yuri insisted we order. That’s the magic of Love Shack—it’s not just a place to eat; it’s a crossroads where lives intersect, even if only for a few hours.

By the time the check arrived, you realize you’ve lingered far longer than intended. The sun has dipped below the horizon, painting the sky in shades of orange and purple, and the Love Shack has turned into a warm cocoon of twinkling lights and laughter. You leave reluctantly, already plotting your return.

The Love Shack isn’t just a restaurant—it’s a sanctuary for anyone who believes that food is more than sustenance, that service is an art, and that the best meals are as much about the soul as they are about the stomach.

Go for the Murg Masalan. Stay for the stories.

5 stars all the way.

From Traffic Cone Chicken to Goa: A Spicy Love Affair

There’s something undeniably electric about boarding a plane bound for Goa. The very name conjures images of vivid spice markets, sun-drenched beaches, and the smoky allure of fish curry simmering on a wood-fired stove. I’ve spent years dreaming of this moment, tracing the flavors and stories that first ignited my obsession with Indian cuisine. Today, I’m finally headed to the source.

I remember the first time Indian food hijacked my senses. I was a teenager, living in a small, gastronomically unremarkable town. My exposure to “exotic” foods was limited to the occasional limp sweet-and-sour chicken at the local Chinese buffet. Then one day, a friend’s family invited me over for dinner. The house smelled of garlic, ginger, and toasted cumin seeds. On the table was a feast—butter chicken, basmati rice fragrant with cardamom, and naan warm from the oven. My first bite was transformative. It wasn’t just food; it was a portal. The layers of flavor, the interplay of heat and sweetness, the unapologetic boldness—I was hooked.

That night, I begged my mother to let me try my hand at cooking an Indian meal for the family. I didn’t know a garam masala from a garbanzo bean, but I threw myself into the task with teenage zeal. I scoured cookbooks, stained my fingers yellow with turmeric, and nearly set off the smoke alarm while charring onions for a curry base. The result? A tandoori chicken so vibrant it looked like a traffic cone and a passable attempt at dal. My dad’s reaction made all the effort worth it: “This is incredible. You should cook more often.”

That summer, we went to France to visit my cousins, and my dad—still raving about the meal—insisted on bringing tandoori spices along. Picture this: a sunlit garden in the french Pyrenees, the air thick with lavender and the scent of roasting chicken wafting from a makeshift grill. My French relatives, skeptical at first, were won over by the smoky, spiced perfection of tandoori chicken. It was a small, delicious rebellion against the tyranny of baguettes and brie.

Now, decades later, I’m chasing that same spark, but on its home turf. Goa, with its Portuguese-influenced cuisine and kaleidoscope of cultures, promises to be a feast for the senses. I’ve daydreamed about sitting at a beachside shack, tearing into prawn balchão with my hands, the tang of vinegar and chilies dancing on my tongue. I want to get lost in the labyrinthine spice markets, where burlap sacks brim with turmeric, cinnamon, and dried red chilies. I want to sip feni, Goa’s fiery cashew liquor, and let it burn its way into my soul.

But more than the food, I’m hungry for the stories. The old fishermen who still haul in their catch at dawn. The grandmothers grinding coconut and tamarind into paste with stone mortars. The street vendors who’ve spent a lifetime perfecting a single dish. Goa isn’t just a destination; it’s a living, breathing cookbook, and I plan to devour every page.

Today marks the start of a journey that’s been simmering for years. And as the plane touches down, I feel that familiar rush of anticipation. It’s the same feeling I had all those years ago, standing in my parents’ kitchen, about to unleash my first attempt at Indian cuisine. The same feeling my dad must have had, introducing tandoori chicken to an unsuspecting French family. It’s the thrill of discovery, the joy of sharing, and the unshakable belief that the best meals aren’t just eaten—they’re experienced.

No one left behind: A Christmas Feast, not a NATO mission

Christmas is a time for breaking bread, clinking glasses, and filling the room with that glorious symphony of voices rising in laughter and good-natured debate. It’s a time when the heart grows larger, the table stretches longer, and chairs are pulled in for anyone who wanders by.

There’s a magic to Christmas that isn’t found in the gifts under the tree or the glittering lights outside. It’s in the clatter of mismatched plates, the warmth of a roaring fire, and the way a kitchen becomes the beating heart of a house, spilling over with smells of roasting meats, spiced puddings, and pies made from recipes that span generations. It’s in the stories we tell—half-true, exaggerated, or just plain ridiculous.

And let's be clear, any proper Christmas gathering starts with cookies - specifically, shortbread. Not those sad, dry store-bought ones that crumble into disappointment, but the real deal. My mom's recipe, passed down with care and reverence, is simple perfection. Simple, rich, and unapologetically buttery, shortbread is the ultimate Christmas handshake—welcoming, warm, and impossible to resist. You don’t mess with shortbread. No icing, no sprinkles, no nonsense. Just flour, sugar, butter, and a touch of salt working in perfect harmony. You offer someone a piece of shortbread, and in that one act, you’ve said, “You’re welcome here. Pull up a chair.”

In a world so often fractured by distance, misunderstanding, and just plain busyness, Christmas demands we put the nonsense aside. It insists we look up from our screens and extend a hand, a glass, a plate. It’s not about perfection. The turkey might be a little dry; the gravy, too salty. But none of it matters when the house is alive with noise and the kind of joy that comes from being part of something bigger than yourself.

And if there’s one rule to live by during Christmas—or any time, really—it’s this: leave no one alone. Not the cranky old guy who sits at the end of the bar nursing his pint of bitter. Not the neighbor who just moved in and whose name you still can’t quite remember. Not the cashier who wishes you a polite “Merry Christmas" or or our now woke PC "Happy Holidays” but looks like they haven’t heard it said back to them all season.

This time of year is about more than friends and family. It’s about strangers who, even for one meal, stop being strangers. Who become, for a few hours, part of the sprawling, imperfect mess of your world. It’s the kid who shows up with their college roommate in tow. It’s the widow down the road who thought she’d eat alone this year. It’s the regular at the pub who’s there every single Christmas because there’s no one waiting for them at home.

Make extra food. Pour another drink. Bake more shortbread. Open your door wider than you think it can go. Invite chaos. Welcome the unplanned. Because the truth is, the more people there are, the better everything tastes. And when the night grows late, and the candles burn low, you’ll find it wasn’t about the gifts or the food or even the booze. It was about them. All of them. The people who turned your Christmas into a kind of messy, beautiful miracle.

So this year, don’t leave anyone behind. Start with a batch of shortbread - trust me, they'll come running. If you’ve got a table, you’ve got a family. And that’s all you really need. And maybe, just maybe, a plate of the best damn shortbread you can make.

93 years of pastry, patience, and pure deliciousness

There’s something enduring about a family recipe. It’s not just food; it’s a map of a life lived well, seasoned with joy and sadness, love and loss, generations of laughter, and the bittersweet passage of time. For 93 years, my mother-in-law—Nana, as everyone affectionately calls her—has been the keeper of one such treasure: her famous jam tarts. A tart? No, not quite. A cake? Almost, but not really. Nana’s Jam Tarts defy categorisation, and maybe that’s what makes them so captivating.

At first glance, they seem simple, almost deceptively so—small, round treats that fit perfectly in the palm of your hand. But behind their unassuming appearance lies a tradition as rich as the strawberry jam nestled inside them. These tarts have seen more holidays, more laughter-filled kitchens, and more plates cleaned of every last crumb than I could ever count. To understand them, you have to understand Nana herself, a woman who’s seen the world shift and change but never lost the core of who she is.

Nana was baking long before Instagram had people worrying about whether their pie had the right kind of lattice, before celebrity chefs were ever a thing. Her kitchen is where real cooking happens—the kind that isn’t about the prettiest presentation or the most exotic ingredients, but about taste, about memories, and about heart. Each year, when the leaves begin to turn and the chill creeps into the air, she gets out the worn, flour-dusted apron and begins her ritual.

There’s a kind of poetry to watching her work, a rhythm to the rolling pin on dough, the careful lining of the cupcake tins with circles of pastry—thinner than you’d think, yet somehow always just thick enough to hold everything together. Each case gets its spoonful of strawberry jam, bright and jewel-like, filling the kitchen with the sweet scent of ripe fruit, a splash of summer in the depths of winter. Then she fills the cases to the brim with cake batter, light and golden, just waiting to puff up and turn into something magical.

When those tarts go in the oven, there’s a kind of hush that falls over the kitchen. Nana’s face—lined with the marks of nearly a century—relaxes, her eyes watchful but softened, waiting for the transformation she’s seen thousands of times. It’s that kind of patience you only get from doing something you love so many times that you could do it blindfolded, from knowing in your bones that good things take time.

Her kitchen, in those moments, feels like a time capsule. There’s no rush, no frantic need to be anywhere else, just the slow rise of the cake batter and the way the jam starts to bubble up at the edges. It’s not about perfection. It’s about the anticipation of what’s to come—the family who will gather, the laughter that will fill the room, the stories that will be shared, the memories that will be made over cups of tea and the sound of a knife sliding through those tarts, cracking the white icing that’s hardened just right.

Nana’s icing is its own story—a simple mixture of sugar and water, stirred by hand until it reaches the consistency she knows by heart. It’s a finishing touch that might seem unnecessary to some, but to Nana, it’s as essential as the jam. Without it, the tarts just wouldn’t be hers. And that’s what makes them special: they aren’t just jam tarts; they’re her jam tarts. They carry her signature, her spirit, and her indomitable sense of tradition.

She’s not one to brag, Nana, but you can see the pride in her eyes when those tarts come out of the oven, golden and steaming, the scent filling the whole house. It’s a pride that’s not about the accomplishment of baking but about the continuity of it—the fact that, year after year, she’s still here, still standing, still making those damned delicious tarts. It’s about knowing that when the world around you has gone mad, you can still pull out your favorite tin, flour your hands, and create something real.

Her jam tarts have seen it all. They’ve been served at weddings, at family reunions, at the kind of long Christmas dinners that stretch late into the night, with a fire crackling in the background and wine glasses clinking. They’ve survived toddlers with sticky fingers, teenagers who are ‘too cool’ to care about family gatherings, and adults who have come back, humbled and hungry for the comforts of their childhood. Nana’s tarts have been there through every moment of joy and sorrow—baked with the same care, the same love, the same defiance in the face of time.

They’re not fancy. There are no shortcuts in Nana’s recipe, no “improvements” to be made. And that’s the beauty of it. Every jam tart is made from scratch, from rolling out the dough to the final brush of icing. There’s no rush, no cutting corners, and no modern gadget that can replicate the way her hands shape the pastry. It’s not about convenience; it’s about doing things the right way because the right way is worth it.

Love listening to Nana‘s stories about the first time she made jam tarts for her own children, long before any of us came into the picture. You get a sense that, for her, these tarts are more than a recipe—they’re a lifeline, a connection to the people she’s loved, the places she’s been, and the years she’s survived. They’re her way of telling the world, “I’m still here. I’m still standing. I’m still baking.”

So when you take a bite of one of Nana’s Jam Tarts, you’re not just tasting sugar, pastry, and jam. You’re tasting history. You’re tasting perseverance. You’re tasting a lifetime of memories, all baked into something small enough to hold in your hand, something so deceptively simple and yet so utterly profound. You’re tasting love in its most enduring, sweetest form. And for that, we all owe Nana a toast. Here’s to 93 years of life, laughter, and jam tarts that will outlast us all—because some things are just too good to ever fade away.

The cultivation of a mouthgasm: lion’s mane mushrooms

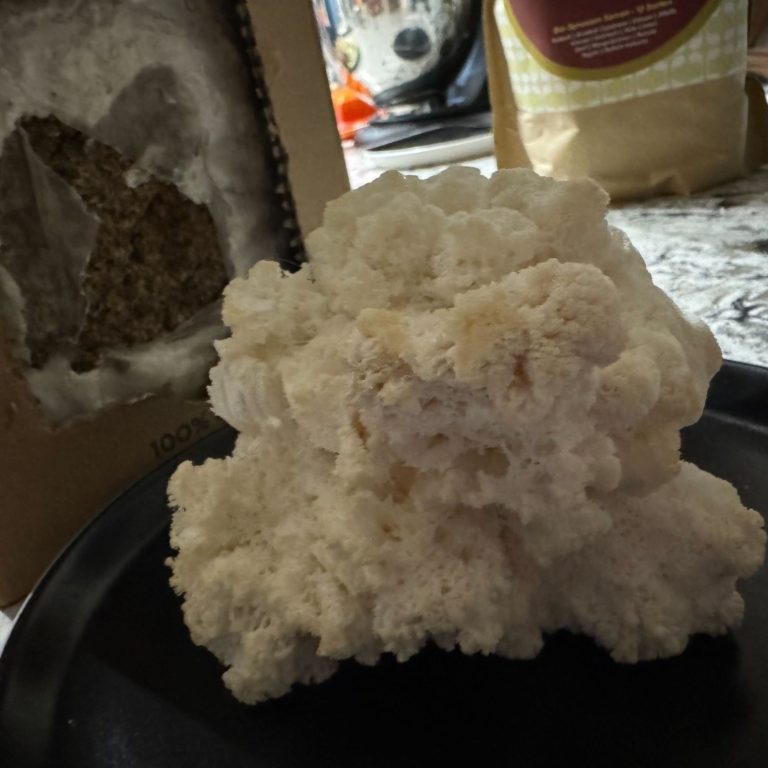

Growing your own food is like alchemy—a dirty, messy magic trick where soil and time conjure sustenance. But growing a lion’s mane mushroom? That’s culinary sorcery of the highest order. This wasn’t just a mushroom; it was a creature from another world, an alien spore that would become my obsession.

I had read about lion’s mane before—its mythical properties, the promises of health benefits, and that intriguing description of its taste: sweet, meaty, like seafood but not quite. But to me, it wasn’t just about the end result. It was about the process, the journey. I wanted to nurture this strange, shaggy fungus from its infancy, watch it transform into something worthy of the kitchen, and, ultimately, the plate.

Lion’s mane doesn’t look like the mushrooms of your childhood. Forget button caps and portobellos; this thing is from another dimension. The first time it sprouted from the block, I couldn’t stop staring. It looked almost sentient, like it might twitch if I looked too hard. The delicate white strands cascaded down in soft spines, like the mane of some mythical lion or the whiskers of an underwater sea creature.

The process of growing it was meditative, almost sacred. It required patience, attention, and the right conditions—mist the block, ensure the right humidity, and wait. Wait while this otherworldly fungus grew into something magnificent. Every day, I watched it swell, its mane thickening, its presence in my home growing more commanding. There’s something thrilling about that kind of anticipation, the knowledge that you’re cultivating something alive and extraordinary.

When the day came to harvest it, I felt almost reluctant to take it down. The spines were soft to the touch, a texture that was both delicate and substantial. But there’s no room for sentimentality in the kitchen. Knife in hand, I sliced it free, marveling at the dense, spongy flesh that promised so much. Lion’s mane doesn’t just sit there like any old vegetable; it radiates potential.

Cooking it felt ceremonial. I heated a skillet, the kind of heavy pan you trust with your best culinary experiments, and let the butter melt into a golden pool with minced garlic (of course). As the lion’s mane hit the pan, it sizzled and hissed like it had been waiting its whole life for this moment. The aroma that filled the kitchen was intoxicating—earthy, nutty, with an undercurrent of sweetness that hinted at what was to come.

The texture was something else entirely. As I turned the pieces in the pan, they browned beautifully, developing a golden crust that hinted at their hidden treasures. The mushroom transformed before my eyes, from strange and shaggy to something rich, refined, and utterly irresistible.

And then, the moment of truth. That first bite. Sweet, meaty, and layered with umami so deep it felt almost indecent. Imagine the tender bite of lobster, the satisfying chew of a perfectly cooked scallop, and the earthy depth of wild mushrooms all rolled into one. It was a sensory overload, the kind of taste that makes you stop mid-bite to process what just happened. A mouthgasm? That doesn’t even begin to describe it.

But it wasn’t just about the taste. It was the story. The act of growing it, nurturing it, watching it transform from a block of spores to a feast. It connected me to the food in a way that’s rare these days, when so much of what we eat comes sanitized and plastic-wrapped. This wasn’t just a mushroom; it was an experience, a journey, a love letter to the alchemy of the kitchen and the magic of nature.

Will I grow lion’s mane again? Without a doubt. The process is addicting, the payoff life-changing, and the result—both in the pan and on the palate—is nothing short of extraordinary. If you’re looking for a food that will challenge your expectations and reward you in ways you never imagined, look no further than this shaggy, sweet, and spectacular fungus. Growing it is an act of devotion. Eating it is an act of worship.

How my cleavage became dessert

Somewhere in the heart of Vendée, on an evening that smelled like pine and lavender, I sat at my cousin Hélène's table. Hélène—a master in the kitchen, a sort of culinary sorceress who could coax joy out of the simplest ingredients—had outdone herself. We’d feasted on roasted meats, delicate vegetables, wine that kept appearing in our glasses like some bottomless miracle, and then, in the sweet lull of that post-dinner haze, she casually mentioned dessert.

I’d heard about the chocolate mousse, the legend of it, really. Hélène guarded the recipe like a state secret, refining it over the years until it was, in her words, “as close as humanly possible to perfection.” There was something reverent in the way she carried it out, set it down on the table like it was a gift to the gods. The mousse was dense, an almost black chocolate, its surface a pristine mirror.

When I took that first spoonful, it was as if every lousy store-bought chocolate I’d ever tasted vanished from memory. This was the real thing: bitter, dark, not too sweet. The texture was rich, almost custard-like, and it coated my tongue with a lingering creaminess that made my eyes close. I let it melt in my mouth, savouring it with the kind of reverence usually reserved for religious experiences. And then, eyes still closed, I asked Hélène, “Can I have seconds?”

She laughed, her voice full of warmth. Hélène was always delighted when people “got it,” when they understood the depth of something she’d spent years perfecting. But it was her husband, Mikael, who seemed the most thrilled by my enthusiasm. Maybe it was the wine, maybe it was the atmosphere, or maybe he just wanted to see a woman helpless in the face of his wife’s culinary prowess. But whatever the case, he grabbed the spoon, scooped a generous dollop, and leaned over to deliver the goods.

Now, it’s important to note, we were all just a little bit drunk. Not sloppy, not out of control, but that pleasant, buoyant kind of tipsy that makes everything funnier and loosens up the social rules. Mikael, bless his well-meaning heart, was overly excited and misjudged his reach. Time slowed down as I watched that spoon wobble in his hand, then dip, tilt, and land with a delicate, wet splat right in my cleavage. The mousse nestled between my collarbone like some absurd, chocolate garnish.

The whole table went silent for a second. Then the laughter started—first Hélène, then Mikael, then me, until we were all gasping for breath. My eyes watered from the absurdity of it, from the sheer hilarity of being draped in mousse in the middle of a family dinner. But it didn’t end there.

Because, in one of those moments that no sober person would ever think to act upon, Mikael—laughing so hard he was nearly in tears—leaned forward and scooped the mousse off my chest with a spoon, then gave up and just leaned in, retrieving the mousse directly. It was, in all honesty, one of the most bizarre and hilarious moments of my life. I was laughing so hard I could barely breathe, doubled over, barely able to look at Mikael without snorting. And as for Hélène, she was howling, red-faced, wiping tears from her cheeks.

It was pure, unfiltered joy—one of those bizarre, ridiculous moments that just lands in your lap like a gift from the universe, no explanation, no agenda. It was an evening where food, laughter, and love all got tangled up together in this silly, unforgettable mess. It was about the people around the table as much as the mousse itself, the sort of moment that’s impossible to recreate.

Years later, I still think about that night. I think about that mousse—rich and dark, a little bitter but smooth as velvet—and the laughter that made it all taste even sweeter. Hélène’s mousse wasn’t just dessert; it was a testament to everything that makes life worth living.

Cornflakes and comfort: Remembering Elske

Elske was one of those people who seemed born to make others feel at home. She had a rare warmth that wrapped around you like an old sweater—well-worn but never tired. Elske’s presence, much like her cooking, was straightforward, comforting, and surprisingly layered. Her signature potato casserole dish was an unassuming masterpiece that felt both absurd and perfect, like her: creamy, cheesy hash browns, topped with crunchy cornflakes. Sounds odd? Maybe. But that dish, like Elske, always showed up just when you needed it most.

Whenever a gathering needed a bit of brightness or a reminder of the simple joys in life, in would walk Elske with her casserole. She’d set it down as if it were nothing special, and yet, it was always the first dish to disappear. No one made anything quite like it. Potatoes in a sea of cheese, bathed in cream, with a layer of cornflakes somehow both crisp and soaked with flavor—a dish that paired with anything and brought out the best in whatever it was served with.

It’s not easy to put into words what makes someone like Elske so special. But her dish says it better than I ever could. It’s humble but unforgettable. It doesn’t demand the spotlight, but when it’s missing, you feel it. Elske’s casserole—like the woman herself—was an unpretentious comfort. She could bring harmony to the chaos, showing us that no matter what madness life threw at us, a good dish and a warm heart were things we could count on.

Elske wasn’t flashy, and her casserole wouldn’t win any culinary awards. But in a world that worships what’s new and edgy, she offered something much rarer: tradition, trust, and the warmth of real connection. And now, at every gathering to come, we’ll look at the table, and if there’s no dish quite like hers, we’ll know something’s missing. The world is a little less complete without her, but when I think of that creamy, crunchy casserole, I’ll remember that a life well-lived is like a recipe shared—it lives on in each of us, waiting to bring people together once again.

Cold lentils and German disapproval: My pilgrim bond with Jurgen

There are people you meet on a journey who feel less like strangers and more like long-lost friends—the kind of person who makes you wonder if maybe, just maybe, you knew each other in another life. Jurgen was that kind of guy. A towering, bear-like German with a voice like rolling thunder and a heart soft as a monk’s robes. We met on the Camino de Santiago, that ancient path where people walk to lose themselves and maybe find a sliver of meaning among the dust, sweat, and the simplicity of human connection.

Jurgen was more than a presence; he was a force, a spiritual juggernaut. You couldn’t help but feel the world settle a little with him around, his kindness as undeniable as his physical heft. It was as though he’d come into the world just to make other people feel safe, seen, and maybe just a little more alive. If you needed something—a spare bandage, half his water, or even his last sandwich—he’d hand it over with a smile. Generosity was in his bones, embedded so deeply you could practically see it in his walk.

So, when he invited me to Stuttgart for Cannstatter Volksfest, I booked a flight from Canada without a second thought. I arrived, jet-lagged and starving, to a warm welcome, a few mugs of beer, and a feast waiting for me courtesy of Jurgen’s sister, who seemed to have cooked the entire regional repertoire of Swabian classics. But the standout was the Schwäbische Linsen mit Spätzle und Saitenwürstchen—Swabian lentils with spaetzle and sausages. This was food so rich, earthy, and unpretentious that it tasted like it had been simmering for centuries in the kitchens of the Swabian countryside.

The lentils were perfect: creamy and tangy, slightly sweet, and hearty enough to make you wonder if you’d ever really eaten before. That first taste, after a day of travel and a few too many German beers, was a revelation. But as with all great meals, it was about more than food. This was a warm, handmade, memory-soaked bowl of pure comfort, made by Jurgen’s sister, as if she was feeding a long-lost family member.

Jet lag hit hard that first night, and around 4 a.m., I found myself in Jurgen’s kitchen, stomach grumbling, my brain foggy but my mission clear. I needed those lentils. I opened the fridge, eyes bleary, and there they were, cold but still as enticing as ever. I grabbed a spoon and tucked in, half-asleep, standing there like a culinary outlaw caught red-handed.

Of course, I turned to see Jurgen himself, staring at me from the doorway, a look of pure German horror plastered on his face. I was desecrating his sister’s beautiful meal with all the grace of a sleep-deprived Canadian caveman. His mouth twisted with disapproval, but he didn’t say a word. From then on, I became the “cold-lentil criminal” in his mind—a repeat offender.

And yet, every time I came back to visit, there it was: a bowl of lentils waiting in the fridge, chilled and ready for my next early morning raid. Despite himself, Jurgen kept up the tradition. Maybe he was still disgusted, or maybe he’d finally accepted my strange rituals. Either way, he’d have that bowl of lentils waiting.

I think about Jurgen often, how his kindness was as steady as the Camino path itself, always generous, always present. In every bite of those cold, forbidden lentils, there was the warmth of a friendship that never needed words, just a quiet understanding shared over bowls, beers, and a strange, unbreakable bond formed on an ancient trail.

The candy apple: Sweetness with a dash of darknesst

Somewhere in the dark recesses of my childhood memories, wedged between paper skeletons and pumpkin guts, lives the candy apple. You know the one – luridly red, glassy, and glossed with just a hint of menace. It wasn’t the type of treat you'd find in the grubby pillowcases we used as candy sacks. It was special, mythical even. Like an artifact found at the witching hour, demanding you eat it with both hands and half a heart.

You’d reach for that candy apple with caution, feeling the stickiness coat your fingers, knowing it was dangerous and not caring. The crisp snap of the shell, the bite of tart green apple underneath that gaudy candy armor – the contrast was addictive. A taste of fall, but also of something darker. There was no way around it. The candy apple was delicious in its deception. A trick and a treat in one.

And that’s where the story turns. Just think about Snow White, biting into that poisoned apple offered by the Evil Queen. A luscious, shiny, irresistible red orb that held promises of sweetness, hiding a brutal betrayal within. As kids, we were captivated by that forbidden, fruit-centric tale of beauty and poison, seduced by a villain who wielded candy like a weapon.

The candy apple taps into that same twisted vein of dark fairytales. It’s a reminder that innocence can be a mere glaze over danger. Sure, there’s no poison in a candy apple (not usually), but there’s still something slightly perverse about it. It’s an indulgence, a sugar-drenched temptation, balanced on the edge of the knife that could slice it.

And it was always the grown-ups who warned us about it, who fed us stories about strangers offering candy with strings attached. As if they hadn’t spent the past month handing us candy by the fistful and telling us to trust in the magic of Halloween. But that candy apple? It was always a little more than a treat. It was a dare.

Maybe that’s why we bit into it with all the excitement and thrill of Snow White herself.

Beefed-up Tuesdays: Noodles, mince, and a one-way ticket to flavour town

There’s an allure to Asian cuisine that feels like wandering through the back alleys of a bustling market, not knowing what’s around the corner but knowing it’ll be damn good. It’s a blend of controlled chaos, where the sizzle of a hot wok and the crackle of chilis create a culinary symphony. Asia doesn’t just teach you how to cook—it teaches you how to eat. You learn to crave the depth, the contrasts, the thrill of the unknown, even in a dish as simple as beef and noodles.

Now, let’s be honest: weekday meals can be a war zone. You’re tired, you’re hungry, and the clock’s ticking down to that first bite of something comforting. But I refuse to believe that "quick" has to mean compromising on flavor or excitement. Some of the best dishes I’ve tasted weren’t the ones that took hours. They were thrown together by someone who knew exactly how to wield a handful of ingredients, a fierce flame, and a moment of clarity.

So, on those weeknights when you’re craving a taste of something that brings the streets of Asia a little closer, you reach for the ground beef and noodles. Not fancy, but powerful in its simplicity. There’s a kind of magic that happens with beef in Asian cuisine—a transformation of a humble ingredient into something bold, earthy, and unforgettable. The beef gets a kick from soy sauce and a touch of sweetness, tempered by the warmth of garlic, the hit of ginger. All those layers. They coat the noodles, each bite becoming this chaotic balance of sweet, salty, and umami. It’s the kind of quick meal that scratches that itch, makes you feel like you’ve traveled halfway around the world, even if your feet never left your kitchen floor.

What I love about cooking this way is that it brings the flavours of a midnight market in Taipei, a side street in Bangkok, or an izakaya in Tokyo right into my home. It’s not about perfecting every note. It’s about capturing the spirit. Cooking this way, even on a Tuesday, doesn’t just fill you up. It wakes you up. Asian flavors don’t leave room for bland. They demand your attention, turn up the heat, and keep you coming back for more.

And after all, isn’t that what the best food should do?

Burned-end eggrolls: A Canadian essential England hasn’t met (yet)

Imagine my dismay—my slow-burn heartbreak—as I scoured England for the perfect, fried crisp of a burned-end eggroll and found, time and again, nothing but silence. The eggrolls I had known back in Canada, delicate bombs of crispy perfection, were nowhere to be found on this side of the Atlantic. You’d think that in a land famed for fish-and-chips’ crunchy, deep-fried exterior, there’d be something on offer like a decent eggroll. I’ve learned the hard way: not so.

Back in Canada, burned-end eggrolls aren’t just on the menu; they’re essential. In every Canadian Chinese restaurant, you’ll find these crackling beauties. They are wrapped a little too tight, fried a little too dark, the edges singed to that perfect crispy crunch where the flavors all pull together. A bit of soy sauce, plum sauce or just take them plain—the right ones don’t need any extra flourish. My absolute pilgrimage-worthy favourite? Golden Palace on Carling in Ottawa, the veritable shrine to all things eggroll. Step in there, order a few dozen to go, and your heart's already on a one-way trip to fried bliss.

But living in England, well, no one even knew what I was talking about. Here I was, obsessed, explaining to friends what they were missing, craving that crunch, and willing to sell my soul for it. So, the mission began: researching, testing, and making so many eggrolls my pub kitchen became a deep fryer in disguise. There were epic failures, rolls so misshapen they looked like sad dumplings, or crisped so far beyond recognition even I couldn’t eat them. But little by little, I got closer, finding ways to fold the dough tighter, to fry it at just the right temp. I had to go to war with these eggrolls, but I was determined to win.

Then, on my last trip back to Canada, I made a beeline for the Golden Palace. I sat down and ordered three dozen to go, packed with care and frozen so they’d survive the transatlantic flight. I had no illusions about eating them fresh out of the bag—this was an undertaking. I was going to reverse engineer these things to finally bring a taste of burned-end heaven back to my own kitchen.

I can’t say I’ve cracked the code entirely, but I’ve gotten close. There’s a whisper of that perfect crunch, a memory of the burned edge in every bite, and a bit of Canada smuggled into each one. England might not know what they’re missing, but in my kitchen, those egg rolls—and all the hours spent replicating them—mean Canada isn’t as far away as it sometimes feels.

24 October 2024

How a bowl of chowder schooled me in the ways of Bermuda

Bermuda—idyllic, pristine, and the kind of place that draws families for its pink-sand beaches and glossy travel brochures. But I wasn’t interested in the perfectly curated tourist experience when I went there as a teenager. No, what captured my curiosity (other than this really cute military guy named Shane) was the grit beneath the glam, the authenticity hidden behind the tropical postcards. And like any great journey, it was the food that taught me the most about the place.

I remember wandering the streets, looking for something real. It didn’t take long before we stumbled upon this little dive, a place that looked like it had been forgotten by time—where paint chipped off the walls and the ceiling fan creaked with every slow, lazy turn. I don’t even remember the name of the joint, but I remember the smell—a mix of fried fish, salt, and vinegar that punched you in the face as soon as you stepped inside. It was like an unspoken promise: you’re about to eat something good.

The fish and chips? Perfection, old-school. Wrapped in newspaper, greasy and unapologetically delicious. The kind of meal where you don’t talk much, just a nod of approval between bites as the flaky, tender fish breaks apart under your fork. There’s a kind of magic in simplicity, in food that doesn’t need to scream for attention because it knows it’s got nothing to prove. This place wasn’t trying to impress tourists; it was cooking for locals. And that’s always a good sign.

But the real revelation? The Bermuda Fish Chowder. I had no idea what I was in for when I ordered it. It was just another dish on the chalkboard menu. I figured, “Why not?” It seemed fitting. And I’d be lying if I said I was expecting much—how good could a bowl of fish soup be, right?

Wrong. So wrong.

It came out steaming hot, dark and rich with a broth that had the depth of a thousand sunsets simmering in it. You could tell it had been bubbling away for hours, flavors merging, transforming, becoming something more. One spoonful, and it was like the island itself was talking to you. There was the briny hit of the ocean, balanced by a warmth that came from deep within the pot, helped along by a splash of Gosling’s Black Seal rum and the island’s secret weapon: sherry pepper sauce. That sauce had heat, but it wasn’t just fire for the sake of it. It was like the wind on the open water, stinging your skin but making you feel alive.

This wasn’t your typical chowder—no cream, no fillers. It was a no-nonsense bowl of soul, filled with chunks of fish that tasted like they were pulled from the water minutes ago. Every bite was an education in the flavors of Bermuda, in the island’s way of mixing the old world with the new, blending British traditions with island spice. I’d never had anything like it, and honestly, I haven’t since.

Bermuda Fish Chowder stayed with me, long after the trip ended. It’s the kind of dish that brands itself on your memory, a marker of time and place that transports you back to that hot, sticky afternoon in a dive that smelled like the sea. The world outside didn’t matter at that moment. It was just me, that bowl of chowder, and the realization that sometimes the best meals are the ones that surprise you—the ones you don’t expect.

Bermuda was beautiful, sure. But it was that damn chowder that made me love it.

23 October 2024

The Fruit Cocktail Cake: A Boozy Legend That Refused to Die

If you’ve spent any time at neighborhood potlucks, you know that every event has its star. Some dishes just don’t mess around. There’s always that one thing that disappears off the table before you even finish your first plate—usually, it’s something like a casserole or fried chicken, maybe someone's secret family chili. But at every potluck I’ve been to in my little corner of the world, it wasn’t any of those. It was my neighbor’s fruit cocktail cake.

Yeah, you heard me: fruit cocktail cake. A Frankenstein dessert made from canned fruit, dripping with booze, and finished off with this unholy liquid icing that seeps into every square inch of the thing. It’s the kind of cake that’s impossible to forget, even if you’re not sure whether you actually want to remember it.

For years, she refused to give up the recipe. My neighbor guarded that thing like it was state secrets. You’d ask, and she’d laugh it off, throw out a “Maybe someday,” then smirk like she was enjoying every second of the mystery. People begged. People tried to reverse-engineer it from memory. They failed, miserably. And so the legend grew, each potluck only stoking the fire.

The thing about this cake is that it had no business being as good as it was. It started with canned fruit cocktail, that old-school monstrosity of diced peaches and pears floating in a syrupy grave. But somehow, this cake transcended that. The moment it hit the table, you’d watch people sidle up, eyeballing the glistening surface, knowing they were about to go in for round two of something they’d promised themselves they’d never eat again.

The kicker? The booze. Disaronno. Almond liqueur. A liquid sugar bomb that drenched the cake to its core. You’d take a bite, and before you even swallowed, that boozy warmth hit the back of your throat. You weren’t just eating cake—you were having a moment. A weirdly nostalgic, slightly tipsy moment, where canned fruit and liquor somehow collided into something dangerously addictive.

The icing was the final punch in the gut. It wasn’t some fluffy buttercream or a drizzle of glaze; no, this icing was liquid sugar on steroids. Poured hot over the warm cake, it soaked in like a sponge. You’d poke your fork into the cake and watch it spring back, saturated with this syrupy madness. It made every bite impossibly moist, as if the cake had been slowly melting into itself. And, frankly, it was kind of obscene.

I tried for years to figure it out. I thought I could nail it—how hard could it be? But it never worked. Mine was always either too dry or missing that hit of flavor that made you come back for seconds even though you knew better. And each time I failed, I’d watch my neighbor show up with her cake, looking smug as hell while people circled it like vultures.

Then, one day, out of nowhere, she gave it up. No fanfare, no buildup. She just handed me the recipe, like she was passing off a grocery list. It was almost disappointing, like the myth was better than the reality. But that’s how these things go, right? You build something up in your head until it’s more than just a cake—it’s a story, an event, a symbol of something you’ll never fully understand. And then, when the truth comes out, you realize that it was simple all along.

That’s the thing about food, though. It’s never just about what’s on the plate. It’s about the memories it kicks up, the stories it tells, the weird way something as basic as canned fruit can become legendary. It wasn’t about the cake—it was about the idea of the cake, the hunt, the secrecy, the anticipation.

But here’s the real kicker. Even now, knowing how simple it is, even though the myth has been cracked wide open, that cake still slaps. I’ve made it a dozen times, and every time I do, people lose their minds. They line up for seconds, thirds, cutting off tiny slices so they can pretend they’re not eating the whole damn thing. It’s a cake that defies logic, like a guilty pleasure that refuses to die, no matter how much you try to rationalize it.

So yeah, the secret’s out. The fruit cocktail cake has been unmasked, and now anyone can make it. But just because the curtain’s been pulled back doesn’t make it any less of a show. It’s still there, on the potluck table, gleaming under the cheap fluorescent lights, tempting you to take one more bite even though you already know better.

Some legends live on, even when the mystery is gone. This cake is one of them.

22 October 2024

Meatballs and Memories: A Tribute to Jim Jenkins

I remember the man before I remember the meatballs, but not by much. Jim Jenkins—my dad’s best friend and neighbor—was a fixture of my childhood, a constant presence who made the world seem a little more grounded. He was the kind of guy who’d show up unannounced to fix a broken gutter or help haul firewood, always wearing that easy grin, the one that let you know things were under control. And then, there were the meatballs.

Jim didn’t just make meatballs; he *crafted* them. These weren’t the limp, bland hunks of meat you’d find in a cafeteria tray. No, Jim’s meatballs were transcendent—spiced with something that was almost alchemical, slow-cooked to perfection, and carrying the kind of flavor that could make you rethink what you knew about comfort food. Every potluck dinner was an event, and Jim’s arrival with a tray of his signature meatballs was like the opening act of a rock concert. People gathered around in anticipation, plates in hand, conversations dropping off as they waited for that first bite.

There was something personal about his cooking, as if every meatball carried a little piece of Jim with it. They were made from the same care and attention that he applied to everything in life. Maybe it was that, or maybe it was just damn good meat, but when Jim was in the room, and those meatballs hit the table, you knew you were in for something special.

Potlucks were a big part of our community. Neighbors brought casseroles, salads, and desserts—but it was Jim’s meatballs that stole the show every time. They had this magical ability to bring people together, to make everyone shut up for a minute and just *appreciate* the simplicity of good food made with love. Jim never bragged about them either—he wasn’t the type. He’d just set them down with a wink and a shrug, maybe crack a joke about how he hoped they weren’t “too spicy” for anyone. Of course, they never were. They were perfect.

Jim was a man who knew how to live well, and I don’t mean in some flashy, high-octane way. He knew how to appreciate the quiet moments, the warmth of a shared meal, the satisfaction of hard work done with your hands. His legacy isn’t just those meatballs—though God knows they’re legendary—but the sense of community he fostered every time he showed up with that tray. In a world that can feel overwhelming and chaotic, Jim Jenkins was a reminder that sometimes the most important things in life are also the simplest: good friends, good food, and a table full of laughter.

Jim’s gone now, but every time I smell a simmering pot of sauce or bite into a meatball that’s just a little bit better than it has any right to be, I think of him. And I smile, because guys like Jim? They don’t come around often, but when they do, they leave you with something unforgettable.

I’d give anything for one more potluck with Jim Jenkins and his perfect meatballs. But more than that, I’d give anything for just one more conversation with the man himself. Because like his cooking, Jim was someone who always left you wanting just a little bit more.

21 October 2024

Beet It: How My Dad Turned a Humble Veg Into Soup Royalty

Borscht—deep, earthy, and unapologetically bold—was more than just a soup for my dad. It was the kind of dish that drew on the marrow-deep satisfaction of hard work and simplicity. Beets, his favorite vegetable, were the heart of it. He saw them as the underdog of the vegetable world: overlooked, misjudged, yet capable of greatness when given the time to shine.

He’d spend hours tending to his borscht, a quiet ritual that began with a small mountain of crimson beets. He knew instinctively when they were perfectly roasted—soft, but with just enough bite to hold their own in the soup. Dad understood that borscht wasn’t about speed or convenience. It was about patience, about coaxing out every bit of flavor from the beets and layering it with the subtle acidity of vinegar and the rich comfort of slow-simmered beef broth.

For him, the beauty of borscht was in its contradictions—sweet but tangy, hearty yet fresh. He’d drop dollops of sour cream into the deep red broth, watching it swirl like clouds on a stormy sky. I’d sit at the table, watching, waiting, knowing that his borscht wasn’t just food—it was a lesson. A lesson that something as humble as a beet could become extraordinary, if you were willing to put in the time, the care, and the soul.

Dad never rushed the process. In his world, good borscht was never just thrown together—it was cultivated. Each time he made it, the soup evolved, as if he were chasing the idea of perfection, knowing full well that the real joy was in the chase itself.

20 October 2024

Duck, Duck... Rice: A Love Affair with Arroz de Pato in Portugal

I’ve eaten my way through a lot of countries. Some dishes I remember because they blew my mind, some because they damn near killed me, and others just because they were there, in the right place at the right time. But then there are the meals that get under your skin, stay with you long after you’ve paid the bill and walked away. Meals that don’t need to scream for attention or come with a Michelin-starred pedigree to knock you on your ass. Meals like Arroz de Pato in Portugal.

It was one of those sticky, golden afternoons in Porto when the light makes everything look like it’s dipped in honey. The city was sweating out the last of summer, the Douro River rolling lazily by, and I was wandering, aimless, jet-lagged, and hungry in that gnawing way that gets louder the more you try to ignore it. I hadn’t come to Porto with a plan. No list of must-visit restaurants, no recommendations. I wanted to feel the place—really feel it—and let it show me where to go.

And that’s how I ended up in a narrow alley somewhere near the Ribeira district, following my nose into a small, unremarkable taverna, the kind of place that feels like it’s been around since Vasco da Gama was still sailing. No fancy signage, no tourists snapping photos for Instagram, just a few locals hunched over plates, heads down, speaking in that rapid-fire Portuguese that’s as much music as it is language.

I knew what I was here for the moment I sat down. Arroz de Pato. Duck rice. I’d read about it somewhere—maybe in one of those travel guides you toss into your bag at the last minute and never look at again. But it had stuck with me. Duck, slow-cooked and shredded, mixed into rice, crispy on top with slices of chouriço. Simple. Honest. The kind of dish that sounds almost too straightforward, like it doesn’t want you to know just how good it really is until you taste it.

The waiter—a man who looked like he’d spent his life in this place, wearing a permanent expression of mild disinterest—didn’t say much. Just a nod, and within minutes, the dish was in front of me.

At first glance, it was underwhelming. A brownish mound of rice with chunks of dark duck meat hiding beneath a layer of crispy, roasted skin. The chouriço—Portugal’s gift to the world of sausages—was dotted around like bright red punctuation marks. No pretensions, no flourishes. Just food.

But the smell... that’s where it started to pull me in. There’s something about slow-cooked duck that wraps itself around your senses like a blanket. It’s heavy, earthy, with that rich, fatty aroma that tells you time and patience have gone into this. And beneath it, the familiar scent of garlic, mingling with the smokiness of the chouriço. I could feel my stomach rumbling, impatient.

I took a bite.

And here’s the thing about Arroz de Pato: it’s not trying to be a revelation. It doesn’t need to be. It’s comfort food, pure and simple, but comfort food with depth. The duck was tender, almost melting into the rice, which somehow managed to be both light and crispy at the same time. The top layer had been roasted to that perfect golden-brown crunch, while the rice underneath soaked up all the juices from the meat, rich with fat, garlic, and that smoky, slightly spicy oil from the chouriço. It was the kind of dish that makes you slow down without even realizing it, savoring each bite because it’s not just about flavor—it’s about texture, warmth, and memory.

This was a dish made by someone who understood restraint. No unnecessary frills, no excessive seasoning, just a balance of flavors that spoke for themselves. It was as if the duck and the rice had been in conversation for hours before I arrived, quietly trading secrets until they reached some kind of understanding. And now, all I had to do was listen.

The restaurant itself was hushed, the afternoon light filtering through the windows, casting long shadows across the wooden tables. I could hear the faint clinking of silverware, the low murmur of Portuguese from the table next to me, but it all seemed distant, like I was wrapped up in this moment with my plate and my glass of local red wine, the kind that stains your teeth and leaves you a little more flushed than you’d like to admit.

By the time I finished, I wasn’t just full—I was satisfied in a way that goes beyond hunger. I felt like I had been let in on something, a secret that had been passed down through generations, from mother to daughter, from cook to cook, always just below the surface of this quiet little country.

As I paid the bill—ridiculously cheap for what I’d just experienced—the old man behind the counter gave me a look. It wasn’t much, just a slight smile and a nod, but in that moment, I felt like we understood each other. No need for words.

Stepping back outside, the heat of the day hit me again, but I didn’t mind. I wandered down towards the river, the scent of duck and garlic still lingering in my memory, mingling with the sound of the city as it carried on, oblivious to the little revelation I’d just had.

Arroz de Pato. It’s not just a meal. It’s an invitation to slow down, to pay attention, to appreciate the simple things done right. It’s the kind of dish that reminds you why food matters—not just as sustenance, but as history, as culture, as connection. And like all the best meals, it leaves you wanting just one more bite.

19 October 2024

Auntie Margaret's amazing chocolate brownies

For many summers growing up, we would file into the car and drive 24 hours to visit the Millard family in Winnipeg... more specifically Auntie Margaret's cottage on Winnipeg Beach. The drive felt endless - hours of farmland and bumpy roads - but it was worth every mile, knowing what was waiting for us at the end: Auntie Margaret's chocolate brownies. Not just any brownies, but the kind you dream about, rich and gooey, with that perfect crinkly top.

I can still see her tiny cottage, white paint chipping on the walls, the smell of lake air and pine trees surrounding us. Auntie Margaret, always in her faded apron, would greet us with a wave from the porch, where she'd sit with a cup of tea and a tin of those famous brownies. With ice cream of course!

18 October 2024