93 years of pastry, patience, and pure deliciousness

There’s something enduring about a family recipe. It’s not just food; it’s a map of a life lived well, seasoned with joy and sadness, love and loss, generations of laughter, and the bittersweet passage of time. For 93 years, my mother-in-law—Nana, as everyone affectionately calls her—has been the keeper of one such treasure: her famous jam tarts. A tart? No, not quite. A cake? Almost, but not really. Nana’s Jam Tarts defy categorisation, and maybe that’s what makes them so captivating.

At first glance, they seem simple, almost deceptively so—small, round treats that fit perfectly in the palm of your hand. But behind their unassuming appearance lies a tradition as rich as the strawberry jam nestled inside them. These tarts have seen more holidays, more laughter-filled kitchens, and more plates cleaned of every last crumb than I could ever count. To understand them, you have to understand Nana herself, a woman who’s seen the world shift and change but never lost the core of who she is.

Nana was baking long before Instagram had people worrying about whether their pie had the right kind of lattice, before celebrity chefs were ever a thing. Her kitchen is where real cooking happens—the kind that isn’t about the prettiest presentation or the most exotic ingredients, but about taste, about memories, and about heart. Each year, when the leaves begin to turn and the chill creeps into the air, she gets out the worn, flour-dusted apron and begins her ritual.

There’s a kind of poetry to watching her work, a rhythm to the rolling pin on dough, the careful lining of the cupcake tins with circles of pastry—thinner than you’d think, yet somehow always just thick enough to hold everything together. Each case gets its spoonful of strawberry jam, bright and jewel-like, filling the kitchen with the sweet scent of ripe fruit, a splash of summer in the depths of winter. Then she fills the cases to the brim with cake batter, light and golden, just waiting to puff up and turn into something magical.

When those tarts go in the oven, there’s a kind of hush that falls over the kitchen. Nana’s face—lined with the marks of nearly a century—relaxes, her eyes watchful but softened, waiting for the transformation she’s seen thousands of times. It’s that kind of patience you only get from doing something you love so many times that you could do it blindfolded, from knowing in your bones that good things take time.

Her kitchen, in those moments, feels like a time capsule. There’s no rush, no frantic need to be anywhere else, just the slow rise of the cake batter and the way the jam starts to bubble up at the edges. It’s not about perfection. It’s about the anticipation of what’s to come—the family who will gather, the laughter that will fill the room, the stories that will be shared, the memories that will be made over cups of tea and the sound of a knife sliding through those tarts, cracking the white icing that’s hardened just right.

Nana’s icing is its own story—a simple mixture of sugar and water, stirred by hand until it reaches the consistency she knows by heart. It’s a finishing touch that might seem unnecessary to some, but to Nana, it’s as essential as the jam. Without it, the tarts just wouldn’t be hers. And that’s what makes them special: they aren’t just jam tarts; they’re her jam tarts. They carry her signature, her spirit, and her indomitable sense of tradition.

She’s not one to brag, Nana, but you can see the pride in her eyes when those tarts come out of the oven, golden and steaming, the scent filling the whole house. It’s a pride that’s not about the accomplishment of baking but about the continuity of it—the fact that, year after year, she’s still here, still standing, still making those damned delicious tarts. It’s about knowing that when the world around you has gone mad, you can still pull out your favorite tin, flour your hands, and create something real.

Her jam tarts have seen it all. They’ve been served at weddings, at family reunions, at the kind of long Christmas dinners that stretch late into the night, with a fire crackling in the background and wine glasses clinking. They’ve survived toddlers with sticky fingers, teenagers who are ‘too cool’ to care about family gatherings, and adults who have come back, humbled and hungry for the comforts of their childhood. Nana’s tarts have been there through every moment of joy and sorrow—baked with the same care, the same love, the same defiance in the face of time.

They’re not fancy. There are no shortcuts in Nana’s recipe, no “improvements” to be made. And that’s the beauty of it. Every jam tart is made from scratch, from rolling out the dough to the final brush of icing. There’s no rush, no cutting corners, and no modern gadget that can replicate the way her hands shape the pastry. It’s not about convenience; it’s about doing things the right way because the right way is worth it.

Love listening to Nana‘s stories about the first time she made jam tarts for her own children, long before any of us came into the picture. You get a sense that, for her, these tarts are more than a recipe—they’re a lifeline, a connection to the people she’s loved, the places she’s been, and the years she’s survived. They’re her way of telling the world, “I’m still here. I’m still standing. I’m still baking.”

So when you take a bite of one of Nana’s Jam Tarts, you’re not just tasting sugar, pastry, and jam. You’re tasting history. You’re tasting perseverance. You’re tasting a lifetime of memories, all baked into something small enough to hold in your hand, something so deceptively simple and yet so utterly profound. You’re tasting love in its most enduring, sweetest form. And for that, we all owe Nana a toast. Here’s to 93 years of life, laughter, and jam tarts that will outlast us all—because some things are just too good to ever fade away.

The cultivation of a mouthgasm: lion’s mane mushrooms

Growing your own food is like alchemy—a dirty, messy magic trick where soil and time conjure sustenance. But growing a lion’s mane mushroom? That’s culinary sorcery of the highest order. This wasn’t just a mushroom; it was a creature from another world, an alien spore that would become my obsession.

I had read about lion’s mane before—its mythical properties, the promises of health benefits, and that intriguing description of its taste: sweet, meaty, like seafood but not quite. But to me, it wasn’t just about the end result. It was about the process, the journey. I wanted to nurture this strange, shaggy fungus from its infancy, watch it transform into something worthy of the kitchen, and, ultimately, the plate.

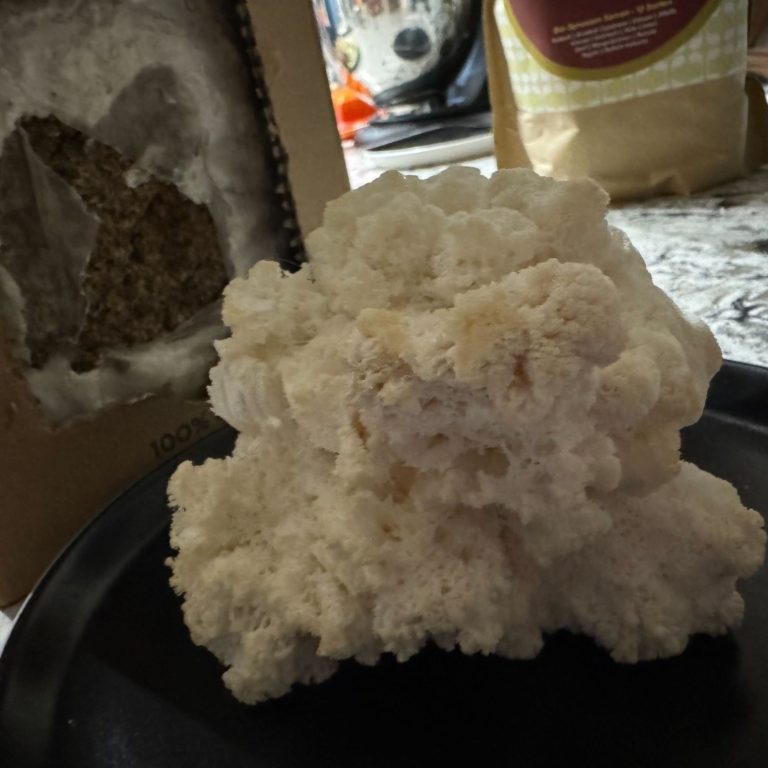

Lion’s mane doesn’t look like the mushrooms of your childhood. Forget button caps and portobellos; this thing is from another dimension. The first time it sprouted from the block, I couldn’t stop staring. It looked almost sentient, like it might twitch if I looked too hard. The delicate white strands cascaded down in soft spines, like the mane of some mythical lion or the whiskers of an underwater sea creature.

The process of growing it was meditative, almost sacred. It required patience, attention, and the right conditions—mist the block, ensure the right humidity, and wait. Wait while this otherworldly fungus grew into something magnificent. Every day, I watched it swell, its mane thickening, its presence in my home growing more commanding. There’s something thrilling about that kind of anticipation, the knowledge that you’re cultivating something alive and extraordinary.

When the day came to harvest it, I felt almost reluctant to take it down. The spines were soft to the touch, a texture that was both delicate and substantial. But there’s no room for sentimentality in the kitchen. Knife in hand, I sliced it free, marveling at the dense, spongy flesh that promised so much. Lion’s mane doesn’t just sit there like any old vegetable; it radiates potential.

Cooking it felt ceremonial. I heated a skillet, the kind of heavy pan you trust with your best culinary experiments, and let the butter melt into a golden pool with minced garlic (of course). As the lion’s mane hit the pan, it sizzled and hissed like it had been waiting its whole life for this moment. The aroma that filled the kitchen was intoxicating—earthy, nutty, with an undercurrent of sweetness that hinted at what was to come.

The texture was something else entirely. As I turned the pieces in the pan, they browned beautifully, developing a golden crust that hinted at their hidden treasures. The mushroom transformed before my eyes, from strange and shaggy to something rich, refined, and utterly irresistible.

And then, the moment of truth. That first bite. Sweet, meaty, and layered with umami so deep it felt almost indecent. Imagine the tender bite of lobster, the satisfying chew of a perfectly cooked scallop, and the earthy depth of wild mushrooms all rolled into one. It was a sensory overload, the kind of taste that makes you stop mid-bite to process what just happened. A mouthgasm? That doesn’t even begin to describe it.

But it wasn’t just about the taste. It was the story. The act of growing it, nurturing it, watching it transform from a block of spores to a feast. It connected me to the food in a way that’s rare these days, when so much of what we eat comes sanitized and plastic-wrapped. This wasn’t just a mushroom; it was an experience, a journey, a love letter to the alchemy of the kitchen and the magic of nature.

Will I grow lion’s mane again? Without a doubt. The process is addicting, the payoff life-changing, and the result—both in the pan and on the palate—is nothing short of extraordinary. If you’re looking for a food that will challenge your expectations and reward you in ways you never imagined, look no further than this shaggy, sweet, and spectacular fungus. Growing it is an act of devotion. Eating it is an act of worship.

How my cleavage became dessert

Somewhere in the heart of Vendée, on an evening that smelled like pine and lavender, I sat at my cousin Hélène's table. Hélène—a master in the kitchen, a sort of culinary sorceress who could coax joy out of the simplest ingredients—had outdone herself. We’d feasted on roasted meats, delicate vegetables, wine that kept appearing in our glasses like some bottomless miracle, and then, in the sweet lull of that post-dinner haze, she casually mentioned dessert.

I’d heard about the chocolate mousse, the legend of it, really. Hélène guarded the recipe like a state secret, refining it over the years until it was, in her words, “as close as humanly possible to perfection.” There was something reverent in the way she carried it out, set it down on the table like it was a gift to the gods. The mousse was dense, an almost black chocolate, its surface a pristine mirror.

When I took that first spoonful, it was as if every lousy store-bought chocolate I’d ever tasted vanished from memory. This was the real thing: bitter, dark, not too sweet. The texture was rich, almost custard-like, and it coated my tongue with a lingering creaminess that made my eyes close. I let it melt in my mouth, savouring it with the kind of reverence usually reserved for religious experiences. And then, eyes still closed, I asked Hélène, “Can I have seconds?”

She laughed, her voice full of warmth. Hélène was always delighted when people “got it,” when they understood the depth of something she’d spent years perfecting. But it was her husband, Mikael, who seemed the most thrilled by my enthusiasm. Maybe it was the wine, maybe it was the atmosphere, or maybe he just wanted to see a woman helpless in the face of his wife’s culinary prowess. But whatever the case, he grabbed the spoon, scooped a generous dollop, and leaned over to deliver the goods.

Now, it’s important to note, we were all just a little bit drunk. Not sloppy, not out of control, but that pleasant, buoyant kind of tipsy that makes everything funnier and loosens up the social rules. Mikael, bless his well-meaning heart, was overly excited and misjudged his reach. Time slowed down as I watched that spoon wobble in his hand, then dip, tilt, and land with a delicate, wet splat right in my cleavage. The mousse nestled between my collarbone like some absurd, chocolate garnish.

The whole table went silent for a second. Then the laughter started—first Hélène, then Mikael, then me, until we were all gasping for breath. My eyes watered from the absurdity of it, from the sheer hilarity of being draped in mousse in the middle of a family dinner. But it didn’t end there.

Because, in one of those moments that no sober person would ever think to act upon, Mikael—laughing so hard he was nearly in tears—leaned forward and scooped the mousse off my chest with a spoon, then gave up and just leaned in, retrieving the mousse directly. It was, in all honesty, one of the most bizarre and hilarious moments of my life. I was laughing so hard I could barely breathe, doubled over, barely able to look at Mikael without snorting. And as for Hélène, she was howling, red-faced, wiping tears from her cheeks.

It was pure, unfiltered joy—one of those bizarre, ridiculous moments that just lands in your lap like a gift from the universe, no explanation, no agenda. It was an evening where food, laughter, and love all got tangled up together in this silly, unforgettable mess. It was about the people around the table as much as the mousse itself, the sort of moment that’s impossible to recreate.

Years later, I still think about that night. I think about that mousse—rich and dark, a little bitter but smooth as velvet—and the laughter that made it all taste even sweeter. Hélène’s mousse wasn’t just dessert; it was a testament to everything that makes life worth living.

Cornflakes and comfort: Remembering Elske

Elske was one of those people who seemed born to make others feel at home. She had a rare warmth that wrapped around you like an old sweater—well-worn but never tired. Elske’s presence, much like her cooking, was straightforward, comforting, and surprisingly layered. Her signature potato casserole dish was an unassuming masterpiece that felt both absurd and perfect, like her: creamy, cheesy hash browns, topped with crunchy cornflakes. Sounds odd? Maybe. But that dish, like Elske, always showed up just when you needed it most.

Whenever a gathering needed a bit of brightness or a reminder of the simple joys in life, in would walk Elske with her casserole. She’d set it down as if it were nothing special, and yet, it was always the first dish to disappear. No one made anything quite like it. Potatoes in a sea of cheese, bathed in cream, with a layer of cornflakes somehow both crisp and soaked with flavor—a dish that paired with anything and brought out the best in whatever it was served with.

It’s not easy to put into words what makes someone like Elske so special. But her dish says it better than I ever could. It’s humble but unforgettable. It doesn’t demand the spotlight, but when it’s missing, you feel it. Elske’s casserole—like the woman herself—was an unpretentious comfort. She could bring harmony to the chaos, showing us that no matter what madness life threw at us, a good dish and a warm heart were things we could count on.

Elske wasn’t flashy, and her casserole wouldn’t win any culinary awards. But in a world that worships what’s new and edgy, she offered something much rarer: tradition, trust, and the warmth of real connection. And now, at every gathering to come, we’ll look at the table, and if there’s no dish quite like hers, we’ll know something’s missing. The world is a little less complete without her, but when I think of that creamy, crunchy casserole, I’ll remember that a life well-lived is like a recipe shared—it lives on in each of us, waiting to bring people together once again.

Cold lentils and German disapproval: My pilgrim bond with Jurgen

There are people you meet on a journey who feel less like strangers and more like long-lost friends—the kind of person who makes you wonder if maybe, just maybe, you knew each other in another life. Jurgen was that kind of guy. A towering, bear-like German with a voice like rolling thunder and a heart soft as a monk’s robes. We met on the Camino de Santiago, that ancient path where people walk to lose themselves and maybe find a sliver of meaning among the dust, sweat, and the simplicity of human connection.

Jurgen was more than a presence; he was a force, a spiritual juggernaut. You couldn’t help but feel the world settle a little with him around, his kindness as undeniable as his physical heft. It was as though he’d come into the world just to make other people feel safe, seen, and maybe just a little more alive. If you needed something—a spare bandage, half his water, or even his last sandwich—he’d hand it over with a smile. Generosity was in his bones, embedded so deeply you could practically see it in his walk.

So, when he invited me to Stuttgart for Cannstatter Volksfest, I booked a flight from Canada without a second thought. I arrived, jet-lagged and starving, to a warm welcome, a few mugs of beer, and a feast waiting for me courtesy of Jurgen’s sister, who seemed to have cooked the entire regional repertoire of Swabian classics. But the standout was the Schwäbische Linsen mit Spätzle und Saitenwürstchen—Swabian lentils with spaetzle and sausages. This was food so rich, earthy, and unpretentious that it tasted like it had been simmering for centuries in the kitchens of the Swabian countryside.

The lentils were perfect: creamy and tangy, slightly sweet, and hearty enough to make you wonder if you’d ever really eaten before. That first taste, after a day of travel and a few too many German beers, was a revelation. But as with all great meals, it was about more than food. This was a warm, handmade, memory-soaked bowl of pure comfort, made by Jurgen’s sister, as if she was feeding a long-lost family member.

Jet lag hit hard that first night, and around 4 a.m., I found myself in Jurgen’s kitchen, stomach grumbling, my brain foggy but my mission clear. I needed those lentils. I opened the fridge, eyes bleary, and there they were, cold but still as enticing as ever. I grabbed a spoon and tucked in, half-asleep, standing there like a culinary outlaw caught red-handed.

Of course, I turned to see Jurgen himself, staring at me from the doorway, a look of pure German horror plastered on his face. I was desecrating his sister’s beautiful meal with all the grace of a sleep-deprived Canadian caveman. His mouth twisted with disapproval, but he didn’t say a word. From then on, I became the “cold-lentil criminal” in his mind—a repeat offender.

And yet, every time I came back to visit, there it was: a bowl of lentils waiting in the fridge, chilled and ready for my next early morning raid. Despite himself, Jurgen kept up the tradition. Maybe he was still disgusted, or maybe he’d finally accepted my strange rituals. Either way, he’d have that bowl of lentils waiting.

I think about Jurgen often, how his kindness was as steady as the Camino path itself, always generous, always present. In every bite of those cold, forbidden lentils, there was the warmth of a friendship that never needed words, just a quiet understanding shared over bowls, beers, and a strange, unbreakable bond formed on an ancient trail.

©Copyright. All rights reserved.

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.